Have you ever stopped to think about what really happens when an explosion occurs near a building or critical piece of equipment?

How do engineers protect people, structures, and essential assets? Explosions caused by industrial accidents, equipment failures, or external threats release incredible energy that can devastate nearby areas in milliseconds. To reduce those risks, engineers rely on walls designed to shield against explosive effects.

Exterior walls of a building can be engineered to provide adequate protection against an explosion. The term “blast wall” however can be a bit of a misnomer. Most people use this term to describe a cantilever free standing wall used to protect an asset, such as a person, place, or thing, from an explosion. Explosions result in a sudden release of energy in the form of a pressure wave, primary fragments from whatever is exploding, secondary fragments that are engaged by the blast wave, heat, light, and sound. Properly engineered blast walls can do a reasonably job at intercepting direct line-of-sight fragments and associated flammable contents. However, they are of little to no or less value at resisting blast pressure waves and trajected fragments. A blast wall can actually increase the blast pressure in some circumstances.

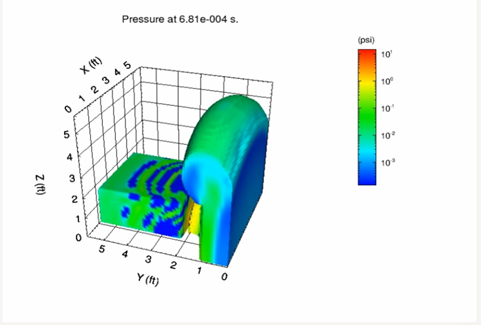

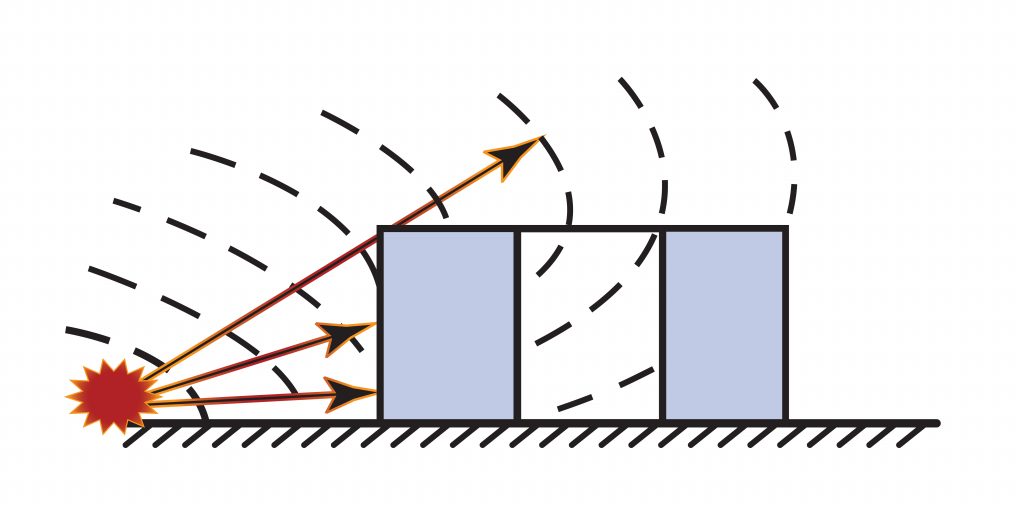

To demonstrate this point, Innovative Engineering Inc. generated the numerical model, a snapshot in time of which is shown in Figure 1. The model was created utilizing computational fluid dynamics or CFD which is a mathematical model of the many cells that make up a gas or fluid. The snapshot shows a blast wall and the pressure wave engulfing the wall and impacting the building behind it. Figure 2 shows the same thing more graphically including the source of the blast wave, blast wall, and what was intended to be protected behind it. As can be seen from both figures, the presence of a blast wall does little to the pressure wave as it reforms behind the wall.

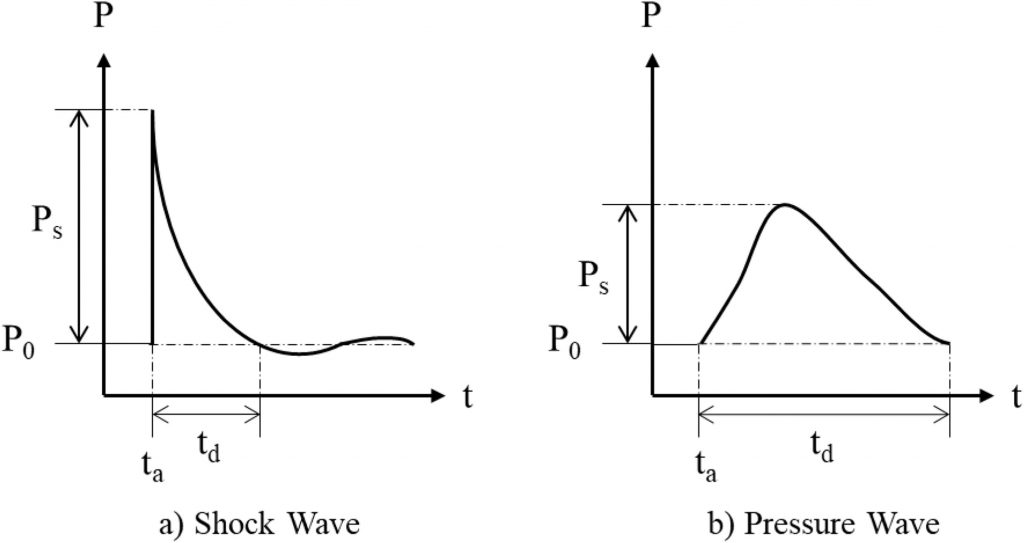

Most engineers simply want to know what single pressure to statically engineer the wall for. As can be seen from Figure 1, the loading is dynamic and varies over a finite time expressed in milliseconds. Furthermore, statically designing the wall for the peak pressure, similar to those shown in Figure 5, is very conservative and results in a very expensive design. Therefore, to engineer an economical design, it is best to design using dynamic loads considering the blast energy absorption properties of the wall or walls.

Explosions occur as detonations resulting in a bang or deflagrations resulting in no bang. In detonations, the shock wave travels at sonic or supersonic speeds. Deflagration pressure waves travel at sub-sonic speeds. Both can also result in the release of a pressure wave, fragments, light, and heat.

Explosions can be the result of “Expansion” or “Oxidation.” Expansion includes a bursting pressure vessel or tank, boiling liquid expanding vapor explosion (BLEVE) such as an electrical transformer explosion, and rapid phase transition (RPT) explosion such as putting dry ice in a water bottle. An oxidation explosion occurs when a substance rapidly combines with an oxidizer, such as oxygen, releasing tremendous energy in the form of a fire and/or detonation. This includes vapor cloud explosions, dust explosions, and condensed phase explosions such as from high explosives.

The initial step to engineering a roof or wall to survive an explosion is to define the loading.

The pressure time-history diagrams above are examples for a detonation shown in figure 5a, and a deflagration in figure 5b. These time histories are produced utilizing testing, computational fluid dynamics (CFD), or empirical equations. In some situations, the explosion loading parameters are prescribed by the building owner or published standards.

The next step is to determine the amount of building damage is acceptable. This can range from a low level of damage allowing the building to be occupied after the explosion to a high level of damage with impaired structural integrity preventing occupancy of the building. The levels of damage in between allow for permanent deformation of the structure. The engineering of the building or component is based on how much energy can be absorbed by the building elastically or recoverable stretching and permanent deformation. An economical design is not based on allowable stress.

The law of conservation of energy states that “energy cannot be created or destroyed, only transformed, or transferred between forms. In an explosion, the explosion transforms potential energy into kinetic energy of fragments and pressure waves, as well as heat, light, and sound. The kinetic energy of the blast wave is absorbed by the strain energy of the structure. This requires mathematical time step integration to solve the equations of energy to determine the amount of deformation.

Utilizing empiracle equations, finite element analysis, computational fluid dynamics (CFD), and testing, the size and velocity of explosion fragments can be predicted. Bullistic data for different wall types can be used to provide adequate wall thickness and strength.

Prescriptive procedures can help simplify the above engineering procedure. One such procedure is published by the National Fire Protection Association NFPA-850. Transformer explosions are generally caused by an internal short-circuit which reaches a temperatute over 2000 degrees farenheit. This high temperature vaporizes the oil creating explosive gases. A lighting strike can accomplish the same thing. This process occurs within milliseconds, too fast for a pressure relief valve to function. To protect adjacent assets including people, buildings, and equipment, either a 2 hour fire wall and/or spatial separation is provided based on the transformer oil capacity. The wall is also designed to withstand wind and seismic loads in addition to the effects of projectiles from the exploding transformer bushings or lightning arrestors. This is accomplished through the use of conventional building codes and UL Standard 752, Standard for Bullet-Resisting Equipment.

Need Blast Design and Protection?

Engineering for blast resistance demands more than simply “building it stronger.” It requires a deep understanding of how energy moves, how materials deform, and how milliseconds can change the outcome. Through advanced modeling, testing, and standards like NFPA-850, engineers can design blast walls and other protective systems that balance safety, practicality, and cost. If you’re responsible for safeguarding facilities or infrastructure, now is the time to evaluate your blast protection strategy—and ensure that it’s grounded in science, not assumptions.